I've been noodling on the kL/r issue for a few days now. In the process, I've realized that my understanding of the nature of those checks has been pretty superficial. Yes, it's a check against "slenderness" but what exactly does that mean and how do you extend that to a non-conventional situation? Here's what I think kL/r means based on the derivation of the equations that we use:

1) You want a member not excessively prone to P-baby-delta moment amplification under axial load.

2) Since apparent flexural stiffness approaches zero as the axial load approaches the Euler buckling load, achieving #1 means controlling the ratio of the applied load to the Euler buckling load.

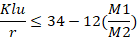

3) To simplify matters for #2, we do the kL/r check without involving the applied axial load. To manage that, we instead assume that the designer intends that the member will achieve some, reasonable ratio of it's squash load (As x Fy, Ag x f'c). Whether that ratio is 0.3, 0.5, or 0.7, I don't actually know.

4) In conclusion, [kL/r < WHATEVER] is a comparison between the Euler buckling load and the squash load of the member. I feel that the important takeaway from this is that the Euler load and the squash load are calibrated to be associated with:

a) The same cross section.

b) materials having the same stiffness.

c) Materials having the same max stress (Fy, f'c).

So, applying this to OP's practical question, here's what I come up with:

A) If OP's steel section is designed to deal with 100% of the moment and axial load, then kL/r < 120 is surely appropriate.

B) If it will be the concrete taking some or all of the axial load then kL/120 will still be appropriate so long as the total axial load does not exceed the squash load of the steel section. That, because in this situation, the steel section alone is still stiff enough against lateral movement that it is capable of stabilizing this amount of axial load whether it resides in the steel or the concrete.

C) If the concrete will take some of the load, and that load is greater than the squash load of the steel section, then kL/r < 120 is no longer appropriate. That, because in this situation, the steel section alone is not stiff enough against lateral movement that it is capable of stabilizing this amount of axial load.