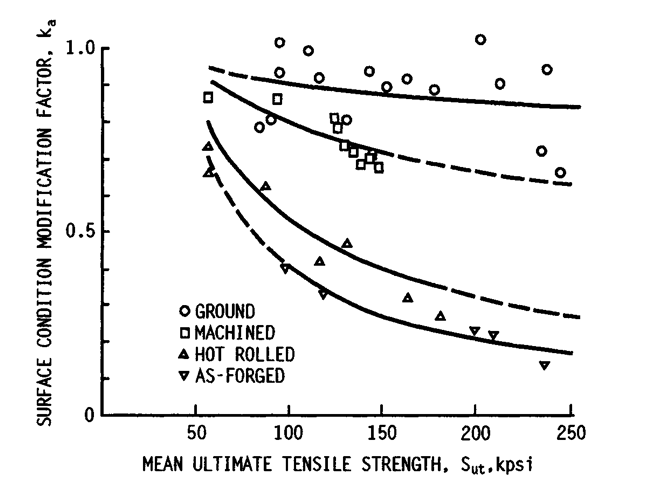

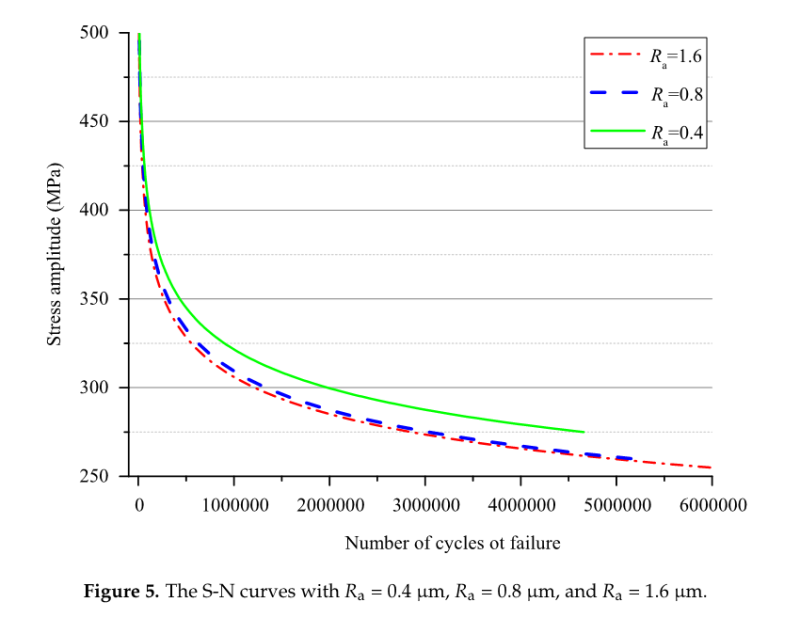

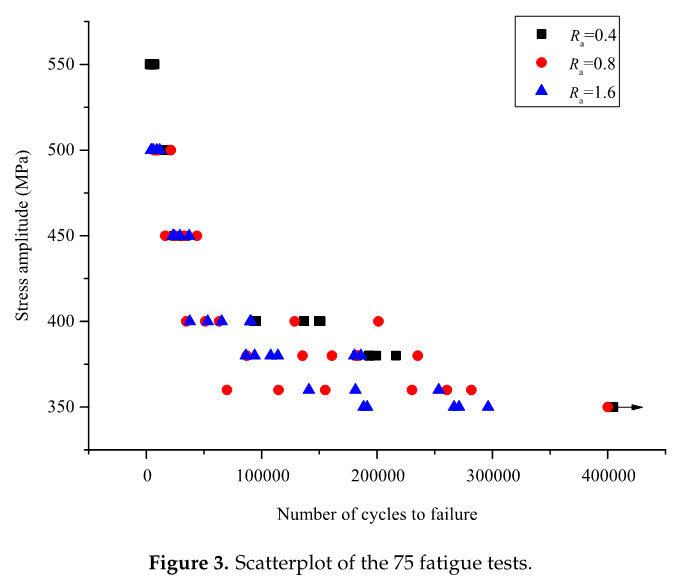

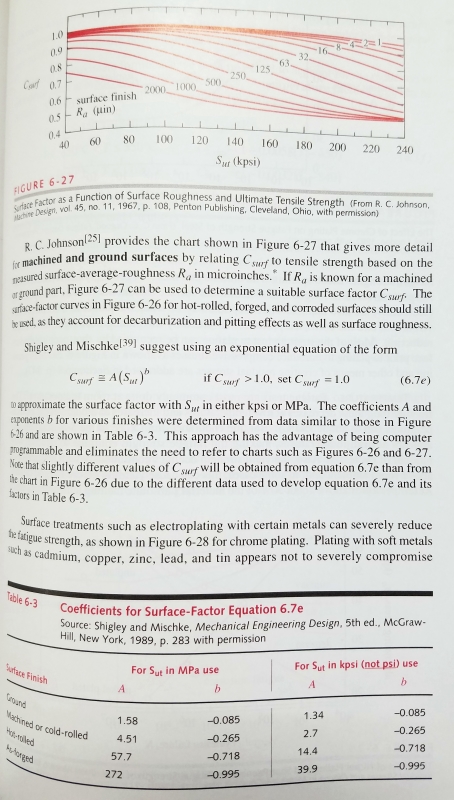

I think it is fair to say that there is a well established relationship between the quality of the surface finish and the fatigue strength of a part. A smoother surface has fewer points in which a crack can begin to propogate and affect the fatigue life of the part. Unfortunately, this general statement doesn't do much to guide design other than to make qualitative statements about the relative fatigue life expectations between two specified finishes.

A few years ago, somehow I came to the conclusion that there was a point in terms of decreasing the quality of a surface finish where there were diminishing returns. In other words, in terms of its impact on fatigue life, there wasn't a huge difference between, say, a 250 and a 125 finish (Ra microinch) - or even a 125 and a 62. At some point though, a fine enough surface finish starts to improve the predicted fatigue life of a part. I can't recall if this was in the neighborhood of 32, 16, 8, etc. though.

Unfortunately, I can't remember how I arrived at this conclusion. I've done a quick search through a number of papers on the subject, and generally they examine 2 or 2 different finishes. Not enough to derive the sort of conclusion I recall making. Does anyone else know of something similar? Perhaps a rule of thumb you use in your company for highly stressed parts?

A few years ago, somehow I came to the conclusion that there was a point in terms of decreasing the quality of a surface finish where there were diminishing returns. In other words, in terms of its impact on fatigue life, there wasn't a huge difference between, say, a 250 and a 125 finish (Ra microinch) - or even a 125 and a 62. At some point though, a fine enough surface finish starts to improve the predicted fatigue life of a part. I can't recall if this was in the neighborhood of 32, 16, 8, etc. though.

Unfortunately, I can't remember how I arrived at this conclusion. I've done a quick search through a number of papers on the subject, and generally they examine 2 or 2 different finishes. Not enough to derive the sort of conclusion I recall making. Does anyone else know of something similar? Perhaps a rule of thumb you use in your company for highly stressed parts?